How have the role and focus areas of boards been evolving as the corporate landscape has changed?

By Karen Loon, IDN Board Member and Non-Executive Director

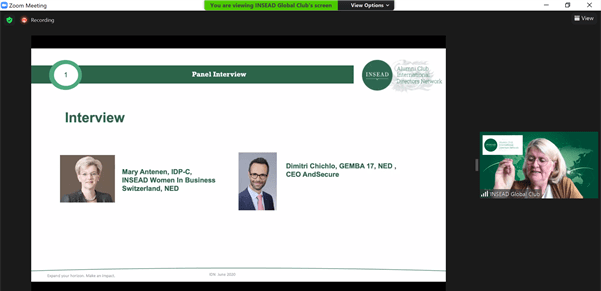

On 16 October 2020, a diverse panel led by Helen Pitcher OBE, IDN President discussed “Confronting Governance Conundrums in an Era of Change” in a session held as part of the INSEAD Directors Forum. Panellists included:

- François Bouvard, Vice Chair of Institut Français des Administrateurs & NED

- Karina Litvack, Non-Executive Board Director, ENI S.p.A., Executive Board Director, Chapter Zero, Member of Board of Governors, CFA Institute, Non-Executive Director, BSR

- Elena Pisonero, Chairperson of Taldig and former President of Hispasat, former Spain’s Ambassador to the OECD; former Secretary of State of Trade, Tourism and SMEs in Spain

The panellists discussed a wide range of topics including:

- What COVID has meant for boards

- Digitisation and data

- Changes in corporate governance in the future

- How will the role of directors change in the future?

What COVID has meant for boards

Over the past nine months, COVID has significantly changed our world. Whilst some companies anticipated some of the changes, others were less prepared for them. For many companies, it has created an acid test for workforces, management and boards who face big challenges ahead. As management may not have enough time to focus on strategy and “reset”, there may need to be a big shift in the roles of management and boards.

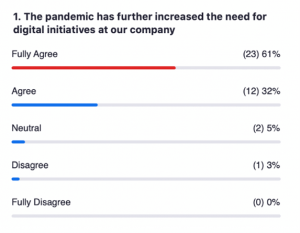

The acceleration of change has also brought to the forefront companies which were less or more prepared due to their digital structures. Those companies which identified the transition of change in society prior to COVID have been transitioning this fairly well compared to sectors which are struggling because they are still doing business in more traditional ways. COVID has emphasised the need for boards and management to work more closely together to identify the future needs of stakeholders at large, not just shareholders.

The pandemic is an example of a systemic risk – something that none of us can solve because it needs to be solved at a systemic level, but all of us suffer the consequences of if it’s poorly managed, therefore, what are we going to do? In considering the systemic impact of the pandemic, a broader question some companies have been considering is do boards understand systemic risk, do they talk about it, do they discuss it? What can they do as companies to influence systemic preparedness, and is there a role for business in influencing the policy environment and the big social infrastructure investments that are made to protect both the society and business environment?

Some panellists feel that it is time for companies, led by their boards to introduce more ‘out of the box’ thinking and change the role of governance. Boards and companies should not only be considering what they can control but think more broadly about all the things that are going on.

Digitisation and Data

Many companies have a misconception or misunderstanding of what digital is – it is what we can do with connectivity but doing things in a different way. Digital technology is the tool which allows companies to better reach their purpose.

Increasing the extent of use of digital should be viewed as a cultural change; it is not a matter of introducing new processes or new titles for the C-Suite. It is how companies combine digital and physical means. Companies need to have a mindset change and consider their whole value chain and how they can better manage and identify best opportunities to change their business models in order to thrive. Companies cannot succeed at affecting this transformation unless they put people at the centre of it.

One suggestion was that in order to be better prepared for more digitalisation, companies should introduce ‘D’ in ESG because we should introduce as much data as we can to improve our decision-making processes. Data is a crucial part of a digital mindset to improve decision making and identify and anticipate future risks.

Changes in corporate governance in the future

Boards are now looking at how they govern their companies more holistically, shifting discussion towards stakeholder governance rather than just shareholder capitalism. Many companies are starting to address human issues (i.e. talent development) more effectively and are connecting the dots in terms of digital to human elements, recognising that at the end of the day that key stakeholders are customers and employees. Digital has been providing companies ways to be more efficient.

Whilst sustainability is more on the mind of everyone, many companies are struggling with shorter term issues, so have pushed some longer-term questions aside for the moment. This will continue if the pandemic drags on. However, boards and management do need to revisit the way they work together on strategy in the longer term. Whilst in the short term, companies may have lost focus on sustainability, in the longer term the view is there needs to be much more focus on this area as companies have a societal responsibility and everything they do should link back to the organisational purpose.

It is likely that the amount of time which boards spend focusing on more “out of the box” discussions in the longer term will expand, given that CEOs and management teams are required to spend much more time on shorter term issues.

How will the role of directors change in the future?

As the whole landscape changes, directors will also need to change. This should start with the board of directors. To be on top of all the issues, not only do they need to be open, read a lot and network well, they need to continue to improve their soft skills to be able to support their CEOs and teams in a supportive and yet challenging way. Boards need to increasingly take a holistic view of their stakeholders, as well as how they support the development of talent, and how they use digital and data. There is also likely to be much more interaction between boards and management, often digitally.