By Luc Albert, Ard W. Valk and Déborah Carlson-Burkart

Organisations are exposed to risks

In September 2011, Kweku Adoboli was arrested, after having caused a loss of over US$ 2 billion for UBS by unauthorized trading at the group’s investment bank. In the following month, the bank’s CEO admitted that the computer system at UBS had detected Adoboli’s unauthorized trading activities beforehand. Although the system had issued a warning, the bank had failed to act upon it.

Over the past two decades, the financial industry has been regularly shaken by cases of such nature. These occurred despite strong regulation, as well as the existence of robust risk frameworks. Underlying causes included fraud or bad intentions, but also human mistakes and mis-interpretations of duties and responsibilities.

In April 2010, the Deepwater Horizon Drilling rig exploded in the Macondo Prospect oil field about 40 miles southeast of the Louisiana coast. The explosion resulted in human casualties – 11 workers died and 17 were injured – an oil well fire and a massive offshore oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. A BP-report, released in September 2010, revealed a series of design errors, operational malfunctioning and human mistakes as main causes for the catastrophe. In September 2014, a US District Judge ruled BP was guilty of gross negligence and wilful misconduct. Transocean and Halliburton, two other companies involved, were fined alongside BP, which was apportioned the bulk of the blame.

The oil industry is known to apply rigorous risk management, given the nature of its operations and potential exposures to its environment. In this industry as well, multiple examples can be found of significant accidents, major pollution and human tragedy, which couldn’t be prevented despite these frameworks.

The Enron scandal publicized in October 2001, resulted in substantially more regulatory scrutiny and led to the implementation of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. The downfall of Enron was caused by wilful human misconduct, incentivized by asymmetric compensation schemes, creative accounting facilitated by the firm’s auditor and a corporate culture focused on misleading internal and external stakeholders.

Risk management framework: a foundation for risk mitigation

A sound risk management approach provides a framework, which typically allows to identifying particular events relevant to the organization’s objectives, assessing them in terms of likelihood and magnitude of impact, while determining a response strategy and a monitoring process, including regular reporting on its design and operating effectiveness. By identifying and proactively addressing risks and opportunities, organisations can protect and create value for their stakeholders, such as owners, employees, customers, regulators, and society at large.

The company’s executive management is responsible for the establishment and implementation of an appropriate risk management framework. Ongoing oversight is sometimes enforced via a dedicated risk management function, led by a member of the executive management team. Today, this is a standard approach for strongly regulated sectors like the financial industry. Internal audit provides assurance.

The board, which has ultimate fiduciary responsibility for determining the company’s strategic direction, plays an important role to assure that risks are appropriately identified and effectively mitigated. After being inducted into the firm’s risk management framework, board members merely receive regular reports from executive management, the internal audit function, as well as external auditors, including ongoing risk assessments, identified exposures and mitigating actions. Applying its collective expertise and experience, the board facilitates identification of oversights and blind spots.

Does this allow the board to effectively fulfil its supervisory role in risk management?

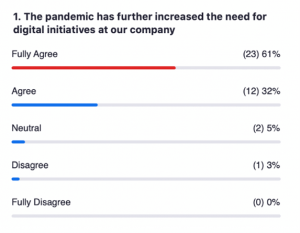

A survey conducted among our IDP 29 cohort members about their own experience revealed a wide variety of risk management approaches in the companies they are engaged in as board members. Not surprisingly, regulated industries appear to have more robust risk frameworks than non-regulated ones. The same applies for larger, more mature companies in comparison to start-ups or smaller companies. Information received is different in quantity, quality and regularity. Moreover, it is often not easy to assess. The amount of time boards dedicate to risk management also differs between companies and industries. Developing a thorough understanding of the company’s core processes as a pre-requisite to fulfil the board’s role turned out to be a common denominator.

Although the examples at the beginning of this article derive from different industries, human behaviour seems to be a decisive factor in all three of them. Whilst risk management frameworks are hardly comparable in quality, rigor and attention, their effectiveness heavily depends on how these are applied by the people involved on a daily basis.

So, why should human behaviour be of interest to board members?

Let us take a step back. The board has ultimate fiduciary responsibility for determining the company’s strategy. This includes stress testing a long-term business plan, its underlying assumptions and main risks. Whilst executive management is mandated to seek growth opportunities, drive innovation and strengthen the company’s market position, it is the board’s responsibility to ensure that the company’s going concern is not put at risk. Or as Timothy Rowley likes to put it: “An effective board acts as an anti-inflammatory, not a growth hormone.”

Once the strategy for a given time period has been approved, the board’s role moves to regular “health checks” which are to a large extent defined by the company’s risk management framework. However, as it appears, it is not enough to have a cognitive understanding of the risk management, processes and controls, as their operating effectiveness ultimately depends on how “risk management is being lived” in daily operations.

As Plato stated in 340 BC: “Good people do not need laws to tell them to act responsibly, while bad people will find a way around the laws”. A crucial element – besides tools and systems – therefore is human behaviour, which is best captured in the risk culture that the company has developed. A vast majority of employees go to work with the best of intentions, using their skills and talents to contribute to the company’s going concern. Setting aside those few who engage in wilful misconduct, fraud or even criminal activities, staff and executives at all hierarchical levels will use their intelligence and judgment to “do the right thing”. At the same time, mistakes are inherent to any human intervention.

Understanding the human factor and risk culture in a company is crucial for the board to effectively operate. Some of the questions that board members should keep in mind: How does the human factor affect risk management in the company? Are mistakes openly addressed and useful lessons learned, leading to improvements of risk management behaviour? What do I, as a board member, have to know about human behaviour and risk culture across the organisation?

In a second article on this topic, we will further assess how understanding human behaviour and risk management culture can be captured as a crucial element for board effectiveness.

Luc Albert, IDP-C is an Independent Board Member.

Ard W. Valk, IDP-C, is a risk manager, Independent Board Member and Independent Risk Advisor.

Déborah Carlson-Burkart, IDP-C, is a lawyer and Independent Board Member.