Company boards have a key role to play in guiding organisations in the digital age.

By Karen Loon, IDN Board Member and Non-Executive Director

To celebrate the first ever digital edition of Global INSEAD Day on 12 September 2020, the INSEAD Directors Network (“IDN”) Global Club held a webinar open to all on “Tech for Good – What is the role of company boards”.

The global panellists were IDN Americas ambassador, Mary Francia, IDN Australia and New Zealand Ambassador, Helen Gillies and Dimitri Chichlo from Switzerland, who are all experienced Non-Executive Directors and INSEAD certified directors (IDP-Cs).

The panel was facilitated by IDN Board Member, Liselotte Engstam based in Sweden with Q&A support from Karen Loon, a fellow IDN Board Member based in Singapore.

Following an introduction by Liselotte Engstam, the panel conversation covered four broad areas:

- How technology aligns to an organisation’s purpose and strategy

- The increasing importance of stakeholder communication

- How can boards best support management in the digital age

- How can current and aspiring board members keep up to speed with developments

Technology should be core to your organisation

All three panellists agreed that today’s organisations must ensure that technology is an integral part of their strategies. With companies facing increasing focus by external stakeholders, whether investors, clients or employees who are holding boards to account, organisations must have a proper purpose, and technology must support that purpose.

As Helen Gillies said, “Technology is just key – it impacts everything that we do; every interface that we have with our external stakeholders, clients, employees, every aspect of our business sales, so it’s just integral. And so that means we must get that strategy around technology right”.

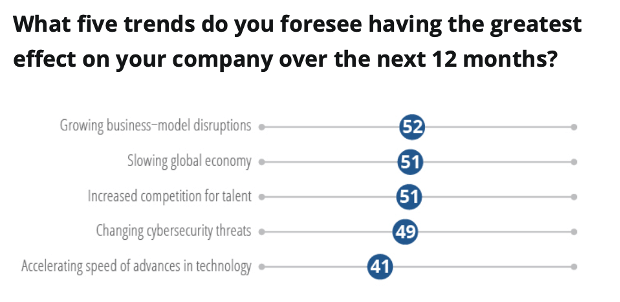

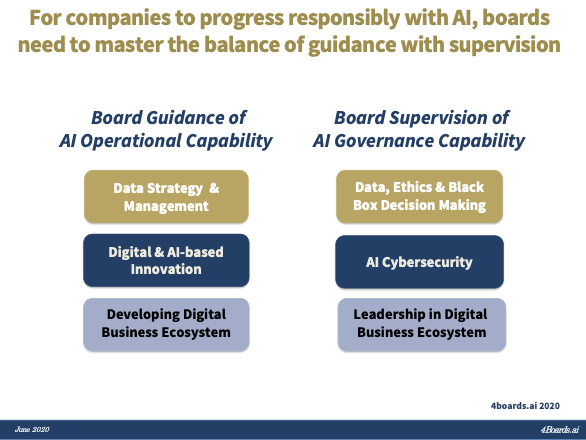

A challenge highlighted by Dimitri Chichlo which boards face is that few boards have people with technology and operations (including cybersecurity) experience, with the majority being business leaders.

Mary Francia added that a question boards need to tackle is how best to manage new risks which are much wider than financial risks – whether technological, geopolitical, environmental, social and governance. “Without the right composition with other vital skills and expertise, you may not have the requisite depth to ask the right questions when it comes to technology, and to support and build what is driving tech for good” said Mary.

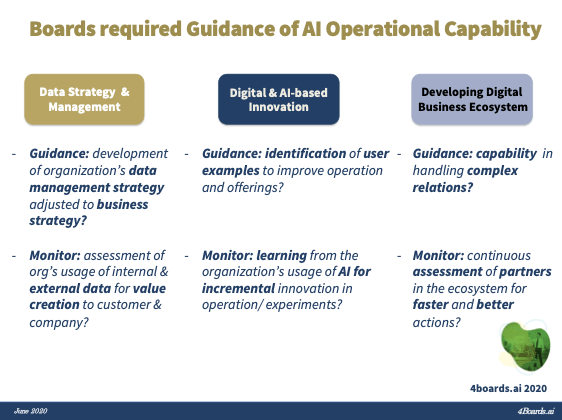

How can boards best support management in the digital age?

According to Helen Gillies, board members have a key role to ensure that the purpose of their organisations are reviewed regularly with management.

“As board members, one thing that’s really critical is we have to be curious. So we have to be looking outside our organisation the whole time thinking what are our clients during, what are our competitors doing, how do we make our organisation better, so that that the concept of being hungry for information is really key” – Helen Gillies

A good practice which Dimitri Chichlo shared on how he supports management was to build rapport with senior leaders outside of the boardroom as soon he started his role to create some proximity with them, which was very much appreciated by management.

Because of increased pressure from investors and stakeholders, to enhance the competence of boards, in addition to more board education to support existing directors, Mary Francia sees more companies looking at their board compositions in detail, and doing board assessments to look at the skill sets of the boards and gaps to identify whether new people should be brought in, committees created or advisors sought. She highlighted the importance of boards having an inclusive culture for change.

The increasing importance of stakeholder communication

All panellists agreed that communicating more broadly about environmental, social and corporate governance (“ESG”) to stakeholders is becoming increasingly important.

Organisations should look beyond their local listing disclosure requirements, and share with employees, communities they work in, clients and investors more about what they are doing. Further, they should understand the stakeholder concerns of their company’s most material stakeholders and ensure that they communicate messages clearly in a language which stakeholders understand. Appropriate board level dashboards on the metrics which really affect the individual company’s business context are important as well as looking at the right outcomes. Finally, having the right accountability, measures, and appropriate links between behaviours and remuneration (which are aligned the purpose of the organisation and its strategy) is crucial.

The panellists also highlighted that having technology and HR competencies on the board, and also ensuring that the management of HR and Technology partner together more closely is also going to be increasingly more important in the future, given that technology should be core to all organisations in the future, and often these two functions are not as aligned as they should be.

Mary Francia also reminded participants of the increasing importance of boards having an inclusive and ethical mind when looking at technology, and how it is applied. Dimitri Chichlo added that this in particular needs to be considered when supporting employees as they adapt in the new world, as technology will impact different generations of employees in different ways.

How can current and aspiring board members keep up to speed with developments?

Our panellists were enthusiastic about the power of IDN’s network, its webinars and its mentoring programme to connect members which are excellent ways for IDN members to engage and keep up to speed.

“… the nice thing is to be able to just get on the phone and talk to one of your directors in Turkey for example or in India, and being able to discuss about a subject because the perspective is so different for every one of them; that that just only enriches and that you just cannot find anywhere” – Mary Francia

Liselotte Engstam highlighted that aspiring directors should seek broad experiences and try to get some P&L experience and run a business to become more familiar with dealing with complexity.

Mary Francia also recommended that aspiring directors gain experience early in their careers in more than one functional area, and “be brave enough to try something different”.

Dimitri Chichlo shared that “…if you work in operations, you will always touch technology, and you will learn on the spot. Whilst books are great, learning with… IT people on the spot gives you an incredible amount of knowledge”. He also mentioned that there are many shorter online programmes available which board and aspiring board members can do to help them keep up to speed with emerging trends and developments in technology.

When considering board roles, panellists however cautioned aspiring directors to ask specific questions to assess whether they are really comfortable with the risk of the organisation and how that organisation does things when things go wrong.

Final advice to board members

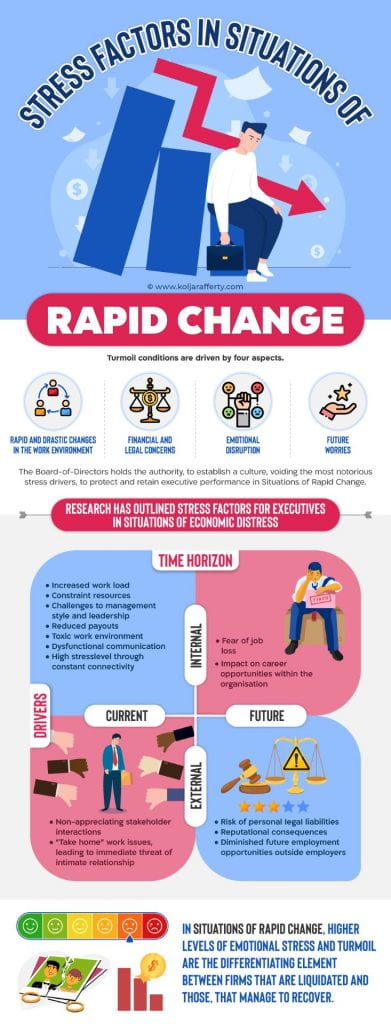

In their concluding remarks, the panellists highlighted that the rapid pace of change with technology, what organisations are doing now will not be what they are doing in another five or ten years. Boards need to anticipate the technological changes and keep up with them. Board members should also ask good questions about whether the organisation is innovative, sustainable, able to adapt to technological changes in the future, accountable and inclusive.

As Helen Gillies concluded, “…the current pandemic has challenged all of us thinking about everything… How do we do things better? How do we challenge our thinking? Because what was normal yesterday is not going to be normal tomorrow”.

A replay of this webinar will be available to INSEAD alumni shortly. IDN’s next webinar for members will be on 16 October 2020, as part of the INSEAD Directors’ Forum.