by Helen Pitcher OBE, Chairman of Advanced Boardroom Excellence Ltd and President of the INSEAD Directors Network, and Ludo Van der Heyden, Chaired Professor of Corporate Governance at INSEAD.

In a changing world, with pressures at global, regional and local levels, the motivations of companies are in the mix. These changes range from a rapidly increasing complexity of the business environment, through to heightened consumer ethical awareness, to a fracturing political landscape.

In this maelstrom of change for companies, there are more and more examples of individual and company role models, who are doing the ‘right’ things at Board level. By ‘right’ we mean moving with the times and reflecting a changing society with emerging values.

Increasingly, companies across the business landscape are recognising the need to measure up to the standards of their customers, consumers, societies and environments in which they operate. These challenges lead companies to be pulled by both global and local demands. That some are moving faster than others is inevitable, and also a consequence of competitive pressures that call for differentiation. But the pressure is on, especially in business with a ‘risk’ exposure to the values of the millennium generation that is even greater than the tension widely felt in politics.

This pressure on businesses goes way beyond a mere focus on gender and minority diversity, it confronts businesses with the case of ‘civil society’ and the need to state themselves clearly in the civil society. It is a human question, and answers based only on simple profit computations will not satisfy the audience in this case. The question calls for a statement of values and a recognition of the responsibility to respond to perspectives broader than individual motivations and myopic self-interest.

While there are and will be many rear-guard actions seeking to sustain the ‘privileges’ of greed and self-interest, the world is, as a result of the globalisation that technology has allowed and made inevitable, becoming closer knit, more informed and more aware of the many faces and forces of diversity. Citizens are naturally looking to governments (local, national and global) and increasingly companies to take collective responsibility to actively maintain their society, their employees and their planet, which is also our planet. In contrast perhaps to governments, there are fewer and fewer hiding places for errant behaviour of individuals and companies. The ‘call-out’ on social and broadcast media is swift and relentless, as the business world becomes more and more transparent. Ironically for many of the social media companies this has also cast a spotlight on their own dysfunctional behaviour. In the UK the recent movement of and investment funds out of the ‘cocoon’ of FTSE regulated governance to off-shore and less transparent jurisdictions has caused a front-page ‘outrage’ that speaks volumes of this new transparency requirement of “the people.”

As the waves of the financial crisis continue to ripple across the ‘pond’, the position of individuals as arbiters of ‘The System’ is seen as increasingly arcane, with the realisation that while the ‘heroes’ of the entrepreneurial world gain the ‘publicity’ for their ‘good, bad and the downright ugly behaviour’, it is the majority of society that overwhelmingly ‘own’ these businesses through their individual savings, their pension funds, and also, for the most fortunate, their sovereign funds.

In sum, there is an increasing focus on the contextual nature of our companies and their position in society regarding the balance of “people, planet and profit” as a priority. The ‘force field’ for these changes comes from a number of convergent pressures; the philosophies of a new ‘brand’ of millennium entrepreneurs, the increasing recognition that employee engagement and sustainability are linked, additionally, the emerging political agenda of worker-owner representatives, and the need for a tax system responsive to the majority and not the 1% is growing in many countries. Single issue pressure groups focusing on gender, environment, ethical supply-chains etc. all add to a consistent, if not increasing pressure for change.

In this post financial crisis era, and also because of it, the ‘people’ movement has found voice. Politicians, in their eagerness to lead, are responding to these ‘voices’ by reflecting them and also by subsuming them into their emerging philosophies, from the ‘Green’ movement to the rising calls for employee representation on Boards. Unlike politicians who are regularly renewed when not thrashed out, most companies do not feel they have this luxury, nor do they wish to embrace seductive but risky and ultimately deceiving populism. They are thus called out to respond, and the place for that debate, both for legal and effectiveness reasons, is the Board.

THE DIVERSITY PREMIUM AT BOARD LEVEL

When we look at our companies’ Boards, they typically reflect astonishingly narrow strata of our society: typically male, typically male accountants, typically ‘aged’, typically technophobes and typically wealthy. This is compounded by the even narrower frame of reference of our typical Chairman, who as leaders of our companies and Boards, are almost exclusively male.

As we look to the present and future, we need Boards and companies that are able to respond to the shifting landscape of society and the breadth of strategic challenges and perspectives faced. ‘The people’ will indeed increasingly look at boards as they should, namely as the place where the corporation defines and assumes its place in society. This in turn requires a deep and hard look at the true diversity of our Boards.

While gender diversity continues at a pace that brings a fresher perspective to our Boards, it does not by itself go far enough. We need a dramatic revision of how we view diversity on Boards, so as to not merely replace male accountants with female accountants. The breadth of diversity on Boards needs a radical transformation to become an active chamber for perspective, debate, discussion and challenge. The competencies and capabilities on our Boards need to range far and wide, beyond the narrow financial oversight of ‘do the numbers add up’, to an external engagement with our customers, employees and society as a whole. While there are a number of exemplar companies that characterise this ‘modern’ board philosophy – and much can be learned from them – they are still in the minority.

We need a diversity of thinking on our Boards that brings a breadth and depth of corporate, functional, cultural, employee, shareholder, environmental and society perspectives. This should be driven by a primacy to facilitate, discuss debate, develop and challenge ideas and strategic intent, and assume the decision and direction ultimately chosen. It is what we might call the diversity premium generated by boards for the companies in their care.

This diversity will continue to prove elusive if we merely look for like for like replacements. We need a mechanism to empower our Nominations Committees to think outside the box. A greater perspective on diversity of thinking and experience is needed enabled by the gender diversity that is now largely accepted.

CALIBRATING DIVERSITY

In practical board terms diversity represents a competition between a narrowness of expertise and viewpoint to achieve financial oversight and a breadth of expertise to achieve strategic oversight. Historically, the emphasis has been on financial expertise, the board’s first language, duly reinforced by the financial crisis which indeed required boards to ‘carefully check the numbers’.

This view rests on the assumption that the financial crisis as a failure of financial understanding, whereas the reality – as identified in numerous reports and books, from the Davies Report onwards – puts the ‘blame’ squarely on Board conduct, and more specifically on behavioural deficiencies of Boards in lacking debate, discussion and challenge of the gaps between the operational performance of companies and their strategic intent. Psychologically, the skills of detailed financial analysis are rarely combined with those yielding a good strategic perspective. Indeed, a number of the most widely used psychological recruitments tools regards these as contra indicators. Diversity again is the answer here.

BUILDING REAL DIVERSITY

We need a better focus on the diversity of Boards that takes us beyond the gender viewpoint into a true diversity of thinking and insight. While additional criteria might be seen as seeking further qualification to ‘block’ more female appointments to Boards, the motivation for gender balance of Board laid in the requirement for much wider perspectives on the skills, expertise and viewpoints of candidates to support much grander diversity of thought and debate, resulting in a step wise improvement in Board effectiveness. While the research is still emerging, the increase of female Board members is seen as having indeed introduced greater diversity to our Boards.

We now need an approach that builds on the existing research and that encourages us to think outside a mechanistic and historical review of Board capabilities, going beyond talking about board diversity as assembling people with different skills and profiles. Time has come to look at diversity in another way: the diversity within each director.

A more detailed look within the profile of each director has several benefits. It reduces the “labelling” or “boxing in” of a director to a single dimension – be it gender, professional, industrial, cultural, or representing ownership – that is pernicious and generally (and rightfully) experienced by directors as negative (e.g. she is our “female” or “minority” director). It stresses the value of directors as contributing a broad portfolio of talents, skills and experiences to the Board. The essential role of the Board is to bring a “balance” of multiple interests and viewpoints. This role is more effectively played by individuals capable of multiple viewpoints and insights. Board dynamics are substantially helped by board members reaching out to others and challenging colleagues with skill and competence on the other side of the argument. It reduces the chances of particular directors exercising their power by virtue of their monopoly on a particular attribute or of the board functioning as a group of silos, board members exercising their views in their silos, and not contributing outside of their silo.

In management the concept of the T-shaped managers is seen as effective, a concept presented by Morten T. Hansen, in his book entitled Collaboration (Harvard Business School Press, 2009). It suggests a core strength, the trunk of the T, with a breadth, the top of the T, to collaborate more effectively with colleagues and facilitate the exchange and furthering of ideas requiring not only a common language, but beyond a common understanding of what the words mean and stand for.

We can also learn from the insights that have emerged from the decision making and behaviour literatures (e.g. Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013) well summarized by Anaïs Nin as ‘we see the world as we are, and not as it really is’. The role of the board is to come to a collective view on issues hopefully ‘as they are,’ and on the risks that particular views may actually be wrong. Individual biases are pervasive roadblocks to excellent board discussion and effective conclusion of these discussions. One-minded individuals may be good for focused execution, but as board members such individuals are generally quite difficult to engage in discussions, have difficulties joining other viewpoints and rarely enrich collective debates that go in directions opposite to their own thinking, let alone admit that they were wrong and happily join the other side. In closing, let us remind ourselves that ‘experts’ are often wrong, be it in economic, military or medical forecasting.

BREADTH OF THINKING

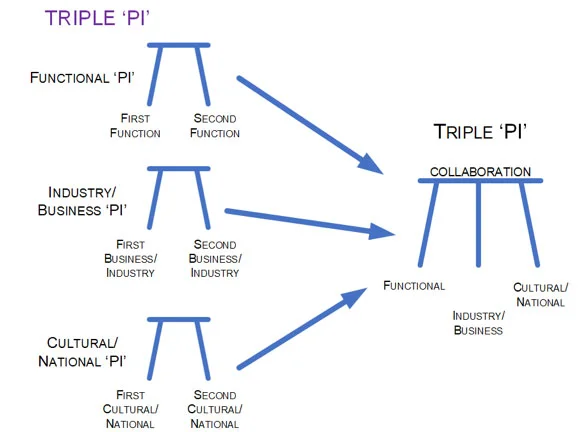

Building on these ideas, and on the work that has characterised effective collaboration amongst managers, there is a benefit from seeking Board directors that are not just T-shaped, but in fact “triple PI” (like the Greek letter ‘π’) or “PI-cubed”.

This view seeks to articulate a broader perspective in the diversity debate concerning Board directors. It seeks to ‘benchmark’ directors on multiple perspectives and ‘drive’ their recruitment against those multiple perspectives, increasing the chances that they might be able to see things both from inside-out and outside-in. These perspectives are:

◼ A FUNCTIONAL ‘PI’, would reduce the bias that comes from being grounded and shaped in one function, valuing directors having at least one other functional strength (e.g. CFO with strong marketing experience). Such a director would more easily provide perspectives not simply emanating from a particular bias rooted in one functional background or expertise.

◼ A Business-industry ‘PI’ would bring a perspective from across differing business sectors and industries, for example mobile phone to banking, music business to mass engagement businesses.

◼ A Cultural-National ‘PI’, the perspective from different cultures and nationalities, again provides a richness of diverse perspective and insight, beyond a particular context or stereotype. Here again the ‘Pi’ dimension is particularly valuable as culture is more easily recognized from a distance and through contrast.

Such a language, if applied, would provide Boards with a rich set of desirable characteristics:

◼ Members would make different and multiple contributions in the skills /experience /competence matrix;

◼ There would be more overlap amongst board members than would appear from the traditional skills matrix;

◼ It would make members appear as composed of a number of ‘slices’ or ‘skills’ – recognizing that board members are both more unique and more diverse than they might be led to appear by traditional methods;

◼ Avoids labelling (like female or digital director) and invites the exploration of the diversity within each board member;

◼ It gives an edge to people who contribute in multiple ways for they can contribute meaningfully to many discussions and through a multiplicity of viewpoints;

◼ It also lays to rest the argument for a “female” director – for when the “female” column is empty the female candidate deserves to be identified first (in terms of bringing value through literally “filling” a hole (or empty column);

◼ It would also allow a better justification of a director appointment in a GM meeting where directors are presented to shareholders (changes the nature of the discussion, by making it more analytical, objective, and rich in nuance and true diversity).

Conclusions

The main point of the argument is that we need to seek diversity in Board members in many more dimensions than is the case for functional executives. It therefore also reminds us that superb but one-dimensional executives do not necessarily make for great Board directors, and that further benchmarking and discussion is needed in such cases.

As the global and also European economic sands shift, the need for a grander vision from the ‘collective’ Board community becomes stronger. The need to build diverse Boards that see beyond the myopic short termism and create profitable, socially aware and people focused businesses has never been greater.

Boards that espouse diversity as part of the solution will do better facing the complexities and turbulences the companies in their care currently face. People and societies demand a more engaged and human business community. The Board population will continue to change with newer, younger more ‘millennial’ viewpoints emerging. As the population of Chairman moves on to a more diverse, more female and more environmentally and socially conscious cadre, this diversity will translate to more strategically expansive and engaged Boards, effectively collaborating to meet the increasingly difficult challenges ahead.

(photo: Pixabay)

(photo: Pixabay) (Photo: Pixabay)

(Photo: Pixabay)

Mary Francia is a Management Consultant in Strategy, Technology & Operational Risk. She is a Certified Director from INSEAD International Directors Programme and Board Member of its IDN Alumni Club.

Mary Francia is a Management Consultant in Strategy, Technology & Operational Risk. She is a Certified Director from INSEAD International Directors Programme and Board Member of its IDN Alumni Club.