By Karen Loon, IDN Board Member and Non-Executive Director

What are the key actions that will increase the likelihood of getting your first board position?

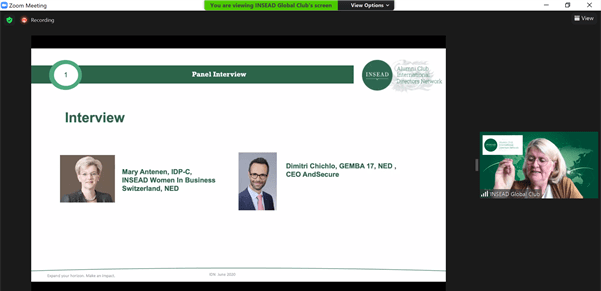

INSEAD Directors Network (“IDN”) members recently had the opportunity to learn more about experiences and insights into the board recruitment process from four experienced IDN members:

- Lorenza Di Giovanni, IDP-C, NED and Executive Search, IDN Ambassador Italy

- Luigi Passamonti, IDP-C, NED, IDN Ambassador Austria

- Susana Gomes Smith, IDP-C, NED, IDN Ambassador Portugal

- Helen Wiseman, IDP-C, NED, IDN Board Member based in Australia

in an exclusive webinar for members held on 1 December 2020 which was facilitated by IDN Board Member, Liselotte Engstam based in Sweden with Q&A support from Hagen Schweinitz, a fellow IDN Board Member based in Germany.

Participants heard from the panellists about their experiences getting their first board roles and growing their board portfolios. They also had the opportunity to also to learn more about how an executive search firm can help directors. Key advice by the panellists included:

- Invest in ongoing board education

- Have a clear vision on what roles make more sense to you

- Do thorough due diligence

- Build your board experience by collecting different facets of experience

- Don’t go it alone – find a mentor and a tribe to share and learn from

- Build your networks

Invest in ongoing board education

- Continuous board education is important for all directors, even if you have had board roles as part of your executive career.

- For international directors, consider both board education in your local market(s) as well as continuous education from programmes such as the INSEAD Directors’ Programme (“IDP”) and subsequently via the INSEAD Directors Network. The IDP programme provides participants with new perspectives including on the values and capabilities which they needed to act as independent directors and allows them gain greater perspective on the role of the board.

- Keep your governance knowledge up to date but keep it practical and fit for purpose.

Have a clear vision on what roles make sense to you

- Do upfront research on what are the geographies, sectors and companies where you can and wish to best contribute. What is your unique selling proposition? How many boards do you wish to be a director on?

- Choose your targets by doing your research – what is the story behind the story i.e., what are they really grappling with at the boardroom table? How might the current composition of the board be playing out? Form a hypothesis and climb into the mind of the Chair. What value do you bring both to the scenario and the different thinking styles and experiences of the board?

- Get clear on your positioning so that people can easily remember you, build a networking plan (see below) based on the above research.

- Prepare well for your interviews.

- Collect your war stories for example from your executive, particularly crises requiring a collective with backbone to work through the issues, or influence across authorities – indicators of how you might perform on a board.

Due diligence

Be thorough on your due diligence on potential board roles. Understand red flags and the culture of the organisation.

Build your board experience by collecting different facets of experience

- Build your board experience by collecting different facets of experience to broaden your value offering for example industries, types of transactions/corporate actions, different stages in the life cycle etc.

- Be willing to start on non-profit organisations and advisory boards.

Don’t go it alone – find a mentor and a tribe to share and learn from

- Don’t go it alone, find a tribe to share experiences with and learn from (for example IDN, your local director association, Women on Boards).

- Find a personal mentor (for example, a senior board director) who can help a new director to fine tune their communication styles for effective board decision making, taking into consideration personal values and styles. This will help you increase your confidence to look for further roles. Consider joining IDN’s mentoring programme.

Networking externally and within your boards

- Make yourself visible and able to be found. Ensure your LinkedIn bio is up to date.

- Let people know that you want board roles (both your close contacts and more broadly).

- Consider doing some public speaking at events or associations or industry specific events, writing a column in a publication or starting a business blog to position yourself as an expert worthy of being considered to sit on a board. IDN members may wish to volunteer to contribute to IDN’s regular blogs.

- If you are not yet on a board, and still in an executive role, see if you can find opportunities to present in front of your current board to get familiar with the board rooms, dynamics, and structure.

- Seek active endorsement and references from people who have seen you presenting and interacting in a boardroom.

- Finally, if you are already on a board, don’t forget to focus on building strong personal relationships with your director peers and management.

IDN’s mentoring programme which is available exclusively for IDN members will be accepting applications in early 2021.