By Kolja A. Rafferty, MBA, IDP-C and IDN Switzerland Ambassador

In professional sports, mental readiness is key for champions. This is highlighting the importance of being mentally balanced also for senior executives. The Non-Executive Board must observe and nurture the mental health of the firm’s top executives in addition to overseeing the firm and acting as the interface between shareholders and executive management, to create resilient and sustainable organizations.

Executives are skilled, able, and well-meaning! Yet, in situations of rapid change, they are observed to act dysfunctional.

Research has shown, executives are skilled, able, well-meaning, and well informed about the firm and its surroundings. In general, they are motivated to pursue the best interest of the shareholders. However, in economic turmoil, executive teams have been observed, to fall into a cycle of dysfunctional communication. This is starting with a state of secrecy and denial, further escalating to blame and scorn, avoidance and turf protection and finally passivity and helplessness.

“Some pressure is good. It makes them run faster!”

A myth in management claims: A level of stress enhances the task performance of the employees. This belief is based on research results conducted in 1908 by the two animal behaviorists Yerkes and Dodson at the animal behavior faculty of Harvard on Japanese dancing mice and has been challenged by various scholars in the past years. Unless the executive team has been recruited from Japanese dancing mice, an increased stress level is diminishing executive performance.

Global sports management is ahead of bespoke management practice

Across different disciplines the global market for professional sports achieved 2019 a total revenue of $ 1.8 billion, leaving an average sports team with a revenue of $ 39.5 mil., in the same spot, as many SMEs. The sports industry is in reality a subbranch of the media and entertainment sector, where task-performance objectives are only on semblance reduced to scoring goals, similarities to business are stronger than one may think.

Muscles and brains cannot be separated from each other. For professional athletes, peak performance is the result of rigorous training regimes and a state of mental readiness. Yet, other than in economics, mental preparation is not left at private discretion but is nurtured by mental coached, preparing athletes for the match. Mental readiness is understood as a critical factor, which is attended with thorough attention.

When it really matters, the framework for top executive performance is at its worst

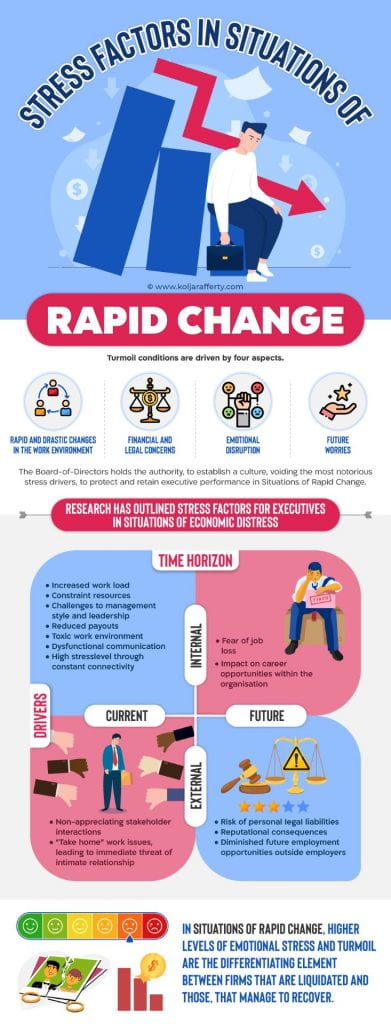

Stress factors, related to situations of rapid change, where the dynamics of the transformation keep accelerating and exceed the level of control of the management, are identified and can be categorized. Excess executive stress under distress and turmoil conditions is driven by four aspects.

- Rapid and drastic changes in the work environment, including increased workload, changes in processes, style, and communication

- Financial and legal concerns, caused by reduced payouts, fear of job loss, potential personal liabilities (et al.).

- Emotional disruption, through continuous and repeatedly non-appreciating communication with various stakeholders, but also including disharmony in the intimate relationship.

- Future worries, for reputational consequences, the continuation of the own career path etc…

Clustering the drivers for executive stress, most stress drivers are triggered by immediate and internal processes. The Board-of-Directors holds the authority, to establish a culture, voiding the most notorious stress drivers, to protect and retain executive performance in situations of rapid change. This can be a foundation for growth and sustainability.

A coach, allowing his team to be mentally distracted before the championship, will be fired on the spot! For a reason!

In situations of rapid change, higher levels of emotional stress and turmoil are suspected to be the differentiating element between the executive teams of firms in distress that must be liquidated and those, that manage to recover.

Capital markets are sensitive to the emotional well-being of the CEO already on a much lower level. Research has proven correlations between the emotional distraction of the experience of a recent divorce and the reactions of the capital markets.

In the 21st century, we are applying executive (self-)leadership of the 1800s

For once, let’s be honest: We all «kind of» know about the risks of Burn-out and the importance of mental health in the Executive world, yet, a stressful workday, permanent connectivity and late hours in the office are treated by many executives as “scares of honor“. Regrettable yet excusable liabilities to the family, the intimate relationship or the own, personal balance and well-being. For career frontlines, this is accepted as the price for success.

In parallel, Executive incentive systems are set up to foster the short term profitability of a firm, yet often fail to include mental balance of the executives in the considerations. It is fair to argue, high paid executives must observe their capabilities to perform themselves, yet, ignoring the relevance of mental balance for executive performance and focus on short term outcomes exclusively, can diminish the resilience of the organization.

In sports this would be equal to send the best player of the team to the match, whilst ignoring recent, previous injuries. Chances are: Small problems will cause bigger problems and end in negative outcomes when it really matters.

A small injury, left unattended, can prove being fatal in the final match.

The Good Coach

For the coach it is key to understand, performance levels vary even for top players. This can be due to daily performance variance, subject to dealing with legacy issues, or emotional burdens. In either case, the result of today’s match may be depending on high performance to be delivered to the point. To win the match the coach must exercise the right assessment of the status of the team and its key players.

For the Chairman, the ongoing monitoring of the capabilities of the executive team is at the core of her responsibilities in order to facilitate long term and sustainable growth and success and foster the resilience of the firm.

Executives are on top of the daily challenges and routines. Even on a “bad day“ they will perform on a sufficient level. Things can turn critical, if the tides are rising. It has been observed, companies, heading for growth and, firms exposed to disruption in the external environment, carry high risk of failure. Resilience is key for the executive team, to deal with situations of rapid change, where the dynamics of transformation keep accelerating and the level of control is diminishing. Here, executives need excess capabilities to control the situation and quickly adapt to a new reality.

For the chairman it is key to understand, if she has the right team in the game. Cheering and motivating, directing from the sideline, bringing in expert players for special situations but also making sure exhausted players rest, and bringing in fresh blood to the match are part of orchestrating a match.

Rigorous training leads to the championship

Success is not born on match day, but build up over the season. Resilience and engagement on the executive level is the result of a process.

To the good, a healthy and well facilitated culture, regular executive education can build up a strong and capable team, able to take on turmoil and situations of rapid change; yet, to the bad, toxic work environments, unhealthy relationships, exhausting periods at work without rest etc. can deplete the resources of the executives and bring individuals close to a point, where breaking sooner or later is inevitable. A little increase in pressure, and the capabilities of the team can be exceeded.

Take away – game changer or playmaker?!

Understanding skills and current capabilities of the executive is at the heart of the chairman’s responsibilities.

Selection, succession planning, challenging, re-training, of the executive team – these are disciplines, easily agreeable to be mastered by the Non-Executive Board. Yet, there is more to it. Identifying and mentoring key players on different levels of the organization, assessing temporary downturns of individual performance and understanding trends vs. events is key to be able to facilitate sustainable success and build resilience throughout the organization. Also, creating a culture, which is aware and hedging for systematic stress drivers, the executive team is facing, specifically in situations of rapid change and moments of turmoil, is key to create value from the board and prepare an organization for rough times ahead.

Kolja A. Rafferty, MBA, IDP-C is an author, consultant and executive. Kolja focuses on situations of rapid change, turmoil and economic distress. He is operating for Private Equity investors and Banks in Europe and the Middle East, helping to resolve distress situations in companies of different sizes and sectors.

First published here.