By Adrian Moors, EMBA (2004), IDP-C, and IDN Mauritius/South Africa Ambassador

What are the learnings from Covid-19 and how are these being utilized in Africa to help enhance governance in a post-Covid world?

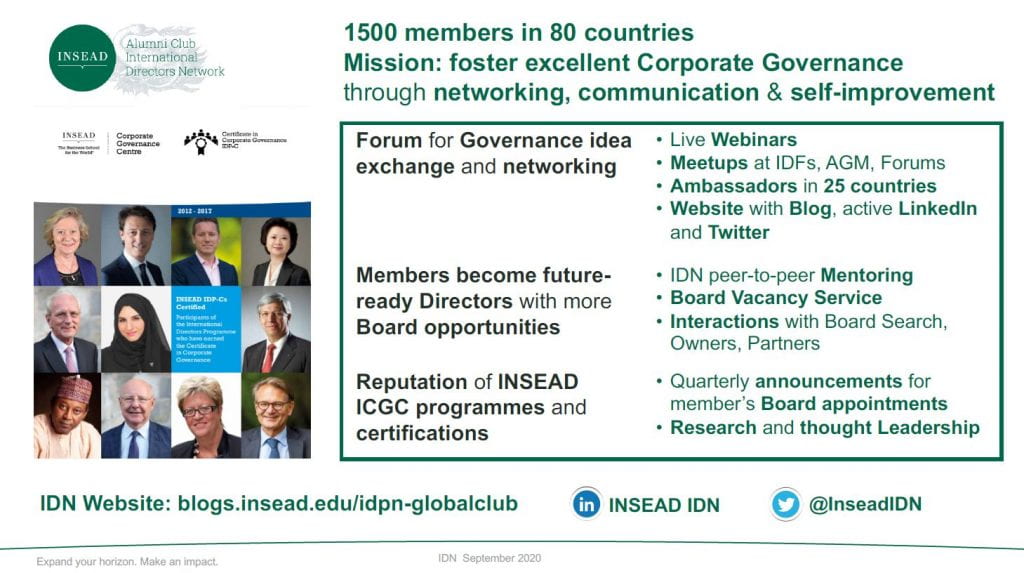

These were the questions discussed in an INSEAD Directors Network webinar, Governance in a post-COVID World – Lessons from Africa held on 4 November 2020.

The webinar was opened by Adrian Moors, EMBA (2004), IDP-C and IDN Mauritius/South Africa Ambassador, and moderated by Liselotte Engstam with support from Hagen Schweinitz, both IDN Board Members.

The panellists were:

- Meshack Joram – Africa Corporate Governance Network Chair

- Alan Barr – KPMG Director, Head of Family Business

- Dr Lucy Surhyel Newman – Independent Director and IDP-C

The key highlights of the discussion were:

- Africa is a complex and challenging environment.

- There are negative perceptions of the continent.

- However, there are also a number of opportunities.

- Corporate governance is critical to realise these opportunities in a sustainable manner.

- There are essential learnings and aspects of governance in Africa that could assist in this regard, particularly in a post-Covid world.

The key points discussed were:

Africa is a diverse continent

There is Anglophone, Francophone, Lusophone and Maghreb Africa. There are a number of programmes, and corporate governance codes being adopted across the continent. Many of these are linked to the King Code and OECD guidelines. Although the codes vary across the Anglophone, Francophone, Lusophone and Maghreb countries, the narrative around Corporate Governance is changing and complexity being removed.

Codes are also being developed and adopted across the Private Sector and State-Owned Enterprises with sustainability becoming a key element through the Global Reporting Initiative Standards.

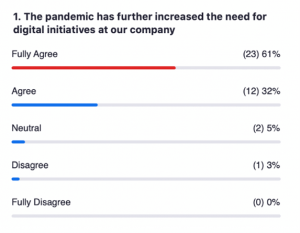

Impact of Covid-19 on corporate governance

Covid-19 has highlighted the need for enhanced governance and sustainability for entities. This is also being supported by governments and the African Corporate Governance Network as composed of Institutes of Directors of about 30 African countries, including through virtual training and networking forums.

For example, following governance challenges within KPMG South Africa, the organisation restructured its board by including a number of non-executive directors and a non-executive Chairman. In order for corporate governance to have meaning and become embedded in an organisation, it has to become part of the culture. This needs to be underpinned in a real manner by the organisation’s purpose and values.

Governance in family businesses is often informal but underpinned by family values and thus embedded. In many instances it is better than that of listed companies. Covid-19 has enhanced family businesses’ clarity of purpose and sense of responsibility towards the communities in which they operate.

Covid-19 has brought about significant changes to corporate governance practices and the manner in which boards operate in Africa, including:

- Regulators having to change and adapt their processes (e.g. allowing virtual Board Committee and Board meetings as well as Annual General Meetings)

- “Paternalistic” and “older” directors being forced to accept a more modern manner of operating.

- Staff welfare being prioritized while also having to develop accountability with remote working.

- The importance of CSR being elevated with companies that have traditionally neglected their social license to operate being penalized in the market.

It has also accelerated the implementation of initiatives such as linking objectives with performance (in the new remote environment), addressing CEO succession and managing risks, the information gap and fair process

The traditional limited transparency around board and organisational operations in Africa is no longer sustainable.

Understanding Africa

Board diversity in Africa is an important issue. It is not just about race, but also language and tribal.

Awareness of this and a local understanding is critical to successfully operate on the continent.

It needs to be addressed and can be done so through the right local structures and representation.

Having a “big bang” approach to improving governance as applicable to the Mo Ibrahim arrangement, is not practical and should be scaled up in a thematic approach to happen incrementally.

Along with the IDN members and ambassadors, other organisations that can assist in addressing this and finding local directors include the Institute of Directors and major accounting firms.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a learning from Africa is that it is essential to embed good corporate governance to protect business for the future and to grow in a responsible manner.