By Liselotte Engstam, IDP-C, NED and Chair, Communication, IDN Board Member

We are facing a period of disruption and disorder, and we need our leaders to show the way. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is one of the crucial technologies for solving our most critical business and society challenges for a more sustainable world. Board work is already a very challenging and complex task, and AI will bring that challenge to a new level.

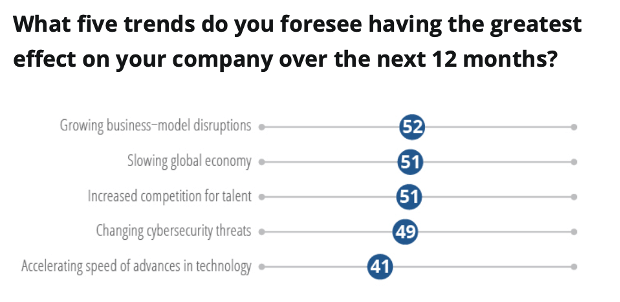

When the National Association for Corporate Directors, NACD did a Survey of Public Company Governance 2019, prior to the pandemic, they found that three of the top five trends with the largest impact were technology related with growing business-model disruptions as the top trend.

Ref: NACD Public Company Governance Survey 2019

Ref: NACD Public Company Governance Survey 2019

With an ambition to find insights to better guide boards, Fernanda Torre, House of Innovation at Stockholm School of Economics & Digoshen Partner, Professor Robin Teigland, Chalmers University of Technology and Board Professional, and I have pursued a two year academic and empirical research on the requirements of Boards Leadership of AI. We found some unique insights on how boards can, without losing themselves in details or in technical jargon, move into the future of corporate governance.

To increase the impact, we decided to share our results in a book: AI Leadership for Boards – The Future of Corporate Governance, which also holds guiding questions that can help boards move forward as they mature.

On 25 June 2020 we held our virtual book launch webinar and were fortunate to have some of our collaborators joining us, as the President of INSEAD Directors Network and Chair on multiples, Helen Pitcher OBE, CEO of Combient Mats Agervi, one of the founding faculty of Singularity University Kathryn Myronuk and MIT scientist researching digitally savvy boards and leadership teams, Stephanie Woerner.

The research was done in collaboration of companies like Combient, a unique joint venture of 30 of the largest Nordic globally operating companies, and FCG Group, a Northern Europe Governance, Risk and Compliance Advisory and Technology Services Company. We based the insights on literature review of both academic and practitioner literature, on deep dive interviews of more than 50 board members and chairmen and AI experts, on several board workshops including note debates notes and polls of 150 board members, and on surveys of 105 board members from across the globe, including the members of the global INSEAD Directors Network.

We have collaborated with INSEAD via guidance from Professor Stanislav Shekshnia and INSEAD Directors Network President Helen Pitcher OBE and with MIT via Dr Stephanie Woerner.

During the webinar we shared insights from the research that highlighted the need for boards to engage, and we shared example of cases and related board questions for boards to ask.

Dr Stephanie Woerner shared results from their research on the impact of Digitally Savy Boards and highlighted related insights of the new research of top teams.

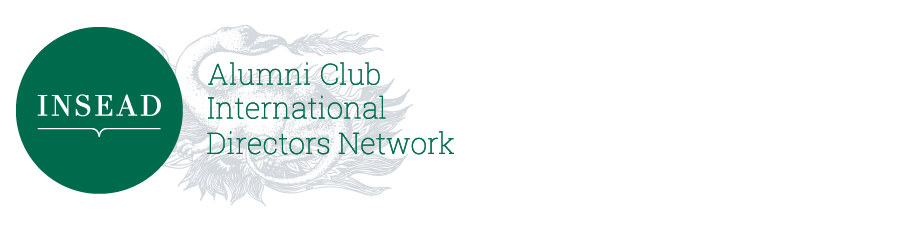

Our findings identified that boards need to develop two competence areas to successfully steward their firms into the new normal. They will increasingly need to learn to balance the [1] guiding of Al operational capability and [2] supervising of Al governance capability.

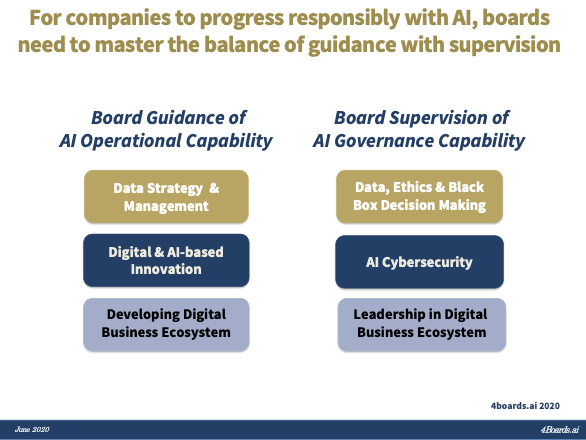

The areas boards need to increase their focus and ambition on are within guiding of Al operational capability:

1) Data Strategy and Management,

2) Digital and AI-based Innovation

3) Developing Digital Business Ecosystem

within supervising of Al governance capability:

4) Data, Ethics and Black Box Decision Making

5) AI Cyber Security

6) Leadership in Digital Business Ecosystem

In the book, we have also summarized guiding questions that can help boards move forward as they mature.

Examples of questions in guiding AI Operational Capability

Examples of questions in supervising AI Governance Capability

The academic research project “4boards.ai”, has been run under the coordination of Chalmers University of Technology and Professor Robin Teigland, with contributions from Digoshen and House of Innovation at Stockholm School of Economics, in collaboration guidance of IMIT, an educational foundation ensuring increased cooperation between academia and industry to improve research validity and speed up the uptake of the results, and with funding from Vinnova – Sweden’s Innovation Agency.

The launch webinar was recorded and can be seen here.

The presentation deck can be found here.

A longer version of this blog can be found here.