By Helen Pitcher OBE, IDP-C, President of INSEAD Directors Network, Experienced Chairman, NED and Board Committee Chair

When we look back at the ‘good the bad and the ugly’ of the Covid Crisis, there will be many lessons to be learnt and best practices reviewed to prepare for any future global pandemic.

Some will be very practical lessons such as the need for quick reactions on key activities like trace and isolation, social distancing and using protective masks.

Some will be structural, such as responding to early warning systems as in New Zealand, or quickly deployable and scalable testing and tracing as in Germany, or rapidly deployable ‘critical care’ hospital capacity as in the UK.

It is largely clear that the countries impacted severely by the earlier SARs local epidemic (it was not officially a pandemic) have sensitised their health systems and citizens to respond effectively to a global pandemic threat and learnt some of the hard lessons the ‘West’ is now encountering, but was initially more sceptical about.

The last globally declared pandemic was in 2009 and the World Health Organisation (WHO) was harshly criticized when this global flu pandemic turned out to be much less severe than people had feared. “Rather than feeling relieved the pandemic wasn’t causing large numbers of deaths, people felt aggrieved they’d been scared over something they later concluded was far less scary than expected” and “governments that had contracts to buy pandemic vaccine — contracts that were triggered by the WHO’s declaration — were left on the hook for a vaccine many people didn’t want.”

There will undoubtably be a whole raft of epidemiology insights and new models preparing for future pandemics, together with a large smattering of hindsight and blame to be apportioned, with Enquiries and Commissions galore.

An increasingly talked about issue, which will undoubtably be part of the post-Covid debate, is the role of female political leader during the crisis. There will be debates over the consensual approach, holding sway in many female leaders’ domains, versus the ‘obey and just do it’ approach in some more authoritarian regimes, which have also proved successful in managing the disease growth.

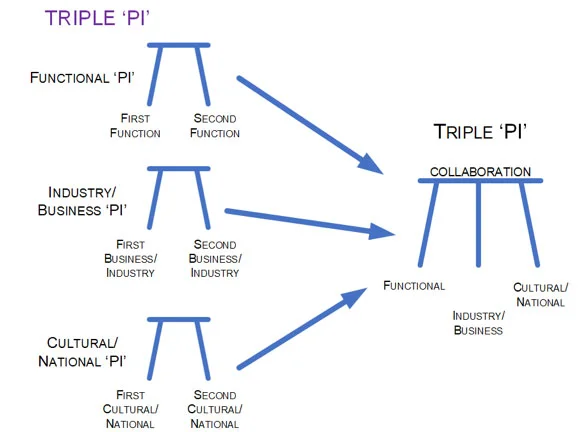

It has been widely reported in the media that we have seen a cadre of female political leadership who have managed a more successful response to the crisis, keeping the spread and contagion low in their countries. This often quoted ‘super seven’ of the ‘Nordic quartet’ of Erna Solberg of Norway, Sanna Marin of Finland, Mette Frederiksen of Denmark and Katrin Jakobsdottir of Iceland, together with New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern and Taiwan’s Tsai Ing-wen is rounded off with the G20 member Angela Merkel of Germany. They are praised for their approaches which have encompassed a range of stereotypical ‘female traits’ of caring, empathy and collaboration, listening to a broad range of diverse views and communicating effectively with the public. These traits have been seen to build trust, transparency and accountability at a time of significant global confusion and panic.

Trust: the long serving Angela Merkel, the Chancellor of Germany, stood up early and calmly told her countrymen that this was a serious bug that would infect up to 70% of the population. “It’s serious,” she said, “take it seriously.” She did, so they did too.

Quick action: by Tsai Ing-wen in Taiwan. Back in January, at the first sign of a new illness, she introduced 124 measures to block the spread without having to resort to the lockdowns that have become common elsewhere.

Clarity and decisiveness: Jacinda Ardern in New Zealand was early to lockdown and crystal clear on the maximum level of alert she was putting the country under—and why. She imposed self-isolation on people entering New Zealand astonishingly early.

Using technology and social media: under the leadership of Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir Iceland offers free coronavirus testing to all its citizens, and instituted a thorough tracking system that meant they did not have to lock down or shut schools. While Sanna Marin the world’s youngest head of state when elected in Finland, demonstrated the skills of a millennial leader in action, spearheading the use of social media influencers as key agents in battling the coronavirus crisis.

Compassion and innovation: Norway’s Prime Minister, Erna Solberg, used television to talk directly to her country’s children. She was building on the short, three-minute press conference that Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen had held a couple of days earlier.

Their rarity as female political leaders with a social caring leadership style, has put these women in the spotlight in a sea of mediocrity and aggressive denial in facing the realities of the Covid crisis.

The analysis of their success is by no means complete and relies, by dint of their rarity, on a small sample of female leaders. It is also, to use that beloved male sporting analogy ‘a game of two half’s’ with the economic impact as likely to cause significant hardship and distress as the contagion phase. We can only hope that the characteristics shown by these women can carry through into the global economic stage, as the world seeks to work together to get the world economy and business working again. The signs, however, are not great, with many of the male dominant G20 leaders seeming to be acting out that other standard from the male playbook of ‘last man standing’, with very self-interested and self-absorbed approaches.

It ironic that following the ‘Financial Crisis’ of 2008, the world was saved from another ‘Great Depression’, by the largely male dominated G7 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors ‘call to arms’, where they worked as one in concert and collaboration to inspire the G20 leaders to co-ordinate and stimulate the world economy to grow again. Notwithstanding that they have much less room to manoeuvre this time, it is difficult at this point, to envisage a similar response from the current global leaders to this crisis, characterised as they are by blame and isolationist approaches, they look more like more subversives than saviours.

It is putting a significant burden on the German Chancellor Angela Merkel, as a key G7 leader, to spearhead this charge alone. Perhaps the newly installed EU female leadership of Ursula von der Leyen as Head of the European Commission and Christine Lagarde as leader of the European Central Bank will add to the proceedings, especially as recent remarks by Christine Lagarde suggest she ‘buys in’ to the concept of caring collaborative female leaders making a difference.

What is clear is that one country alone is unlikely to re-ignite the global economy and it will take those characteristics of collaboration and communication demonstrated by the ‘super seven’ to see us safely through the ‘second half’ of the epidemic.

It is also clear that the adversarial political environments characterised by many of our major economies is less conducive to a collaborative consensus approach, whoever is in charge. It is noteworthy that the majority of the ‘super seven’ have developed and grown in cultures which are more socially orientated with consensus-based politics of coalitions, where compromise and diversity of thinking and inclusion are to the fore.

While the case for women leaders is at this stage more anecdotal than data driven, we can only hope that more women are energised and inspired by the ‘super seven’ to step forward to make a difference and join into the political leadership process.

However, the shift to a less adversarial political process from the “winner takes all approach,” is challenging and problematic, with too many political parties, and backers still focused on getting women to behave more like men if they want to lead or succeed. As articulated by Alice Evans a sociologist at King’s College London who studies how women gain power in public life, this can be difficult for women to meet as “There is an expectation that leaders should be aggressive and forward and domineering. But if women demonstrate those traits, then they’re seen as unfeminine” “That makes it very difficult for women to thrive as leaders.”

As we address more global issues, a consensus style of leadership will become increasingly valuable, with global threats from climate change escalating, creating more ‘natural crisis,’ together with an almost certain greater sensitivity to pandemics. These types of issues cannot be dominated and cowered into submission, they do not respond to the “classic self-obsessed leadership projection of power, acting aggressively and showing no fear.”

These role models of strong female leaders succeeding in a global crisis, send out a strong message to all political leaders. With their success their political status has, grown with their characteristics of curiosity, humility, empathy, and integrity, becoming a benchmark of effective political leadership.

Article first shared here.