By Regine Slagmulder (IDN alumna & former INSEAD faculty member)

The Covid-19 pandemic has been an unexpected shock that is creating extraordinary challenges for companies and their boards on how to navigate uncertain and turbulent times. Previous viral outbreaks rarely made it onto the busy boardroom agendas, but the sheer scale and impact of this crisis has called for undivided board attention. While high-impact/low-probability events are usually very difficult – if not impossible – to predict, it is never too early to start thinking about how to weather the next storm and come out stronger than before. This article argues that boards must spearhead companies’ transformative change in today’s business environment, which is characterized by high velocity, complexity, ambiguity, and unpredictability.

Risk management as a necessary but insufficient condition

As part of their oversight duties, the board of directors is responsible for making sure the company has put in place the necessary risk management capabilities to deal with the negative consequences of unforeseen events. Many companies have made significant progress in implementing adequate risk management systems and procedures, especially in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. They are now better equipped than before to handle incidents through well-established risk registers for identifying risks, information systems that provide appropriate transparency on the downside impact, and contingency plans ready to be enacted whenever disaster strikes.

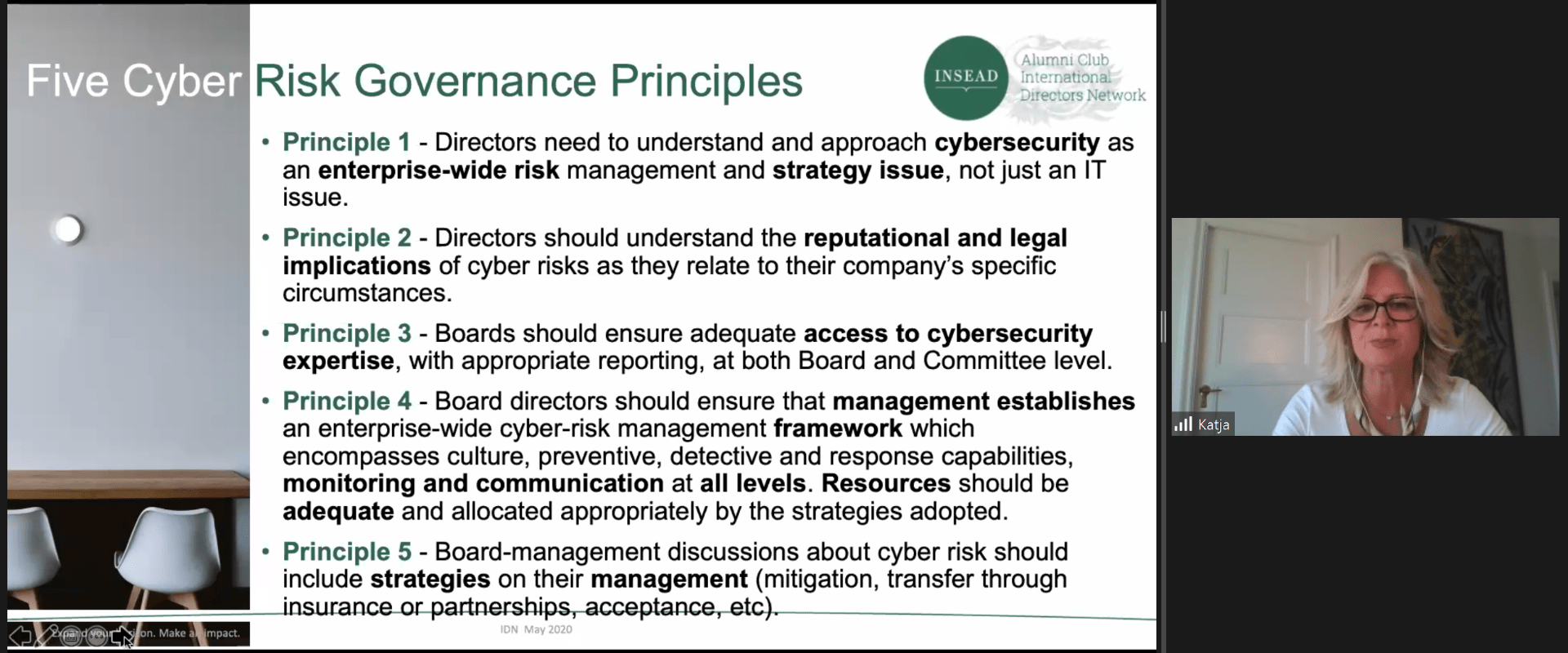

However, there is a major difference between risk events with well-known consequences, such as an industrial accident or a cyber-attack, and unprecedented disruptions, such as the Covid-19 pandemic. The former situations, as overwhelming as their occurrence might be, can be expected to return relatively quickly to the “old normal” after proper recovery measures have been taken. In contrast, the latter events typically do not lend themselves to an existing playbook approach to risk management and are likely to have a lasting impact – not only on individual companies but possibly on entire industries and geographies. While there are clear benefits to putting in place formal risk oversight arrangements, such as quantitative risk analysis and risk committees, to handle the “known” risks, these established mechanisms are insufficient in an environment of deep uncertainty characterized by “unknown unknowns”. Boards must, therefore, elevate their risk oversight role from a routine exercise in operational loss prevention and compliance, to acting as an enabler of long-term corporate resilience.

Boards must, therefore, elevate their risk oversight role from a routine exercise in operational loss prevention and compliance, to acting as an enabler of long-term corporate resilience.

Building resilience: from fragile to agile

While most companies suffer considerably from dealing with an external shock such as the pandemic, some organizations appear to come out of the crisis remarkably resilient. To achieve effective governance, the boards of directors must ensure that the necessary “resilience capabilities” are in place that allow the organization not only to bounce back from a high-impact disruption but also adapt to the new reality more quickly than their peers. These capabilities relate to two key aspects of resilience – preparedness and agility.

First, preparedness refers to the pre-crisis arrangements that the company and its board have put in place to anticipate and proactively mitigate the negative impact of risk events. Examples include information systems for monitoring risk indicators, robust business continuity plans, and slack resources. It also involves actively engaging the diverse set of professional experiences and backgrounds present in the board as well as regularly obtaining outside-in views from external experts. The board’s continuous outlook for what may be coming “around the corner” can significantly contribute to sharpening the leadership team’s sensing skills and detecting strategic risks before they spin out of control. Forward-thinking boards also pressure test management’s assumptions about the longer-term consequences of the virus. Combining these insights and foresights in strategic scenario planning exercises enables boards to take precautionary measures already at an early stage, thus making their companies more resilient to shocks.

Second, agility is required because it is impossible to fully prepare and plan for complex and dynamic situations, especially when it is unlikely that the situation will afterwards return to the pre-shock state of normality. Superior levels of in-crisis adaptation enable companies to take decisions quickly and get ahead of the disruption. The first stage in crisis response is usually one of creative, entrepreneurial problem-solving in real time as the events unfold to secure the company’s immediate survival. Then, as soon as the crisis is under control, the board should stimulate the management team to think proactively about introducing new business models in the “new normal”, for example by accelerating investments in digitalization. As such, it is important to make a shift from the classic mindset of mitigating downside risk to becoming more opportunity driven. Board members need to proactively engage with their executives to discuss how even highly adverse events, such as the Covid-19 crisis, might be leveraged into strategic opportunities to be exploited in the longer term. For example, companies might consider acquisitions targeted at growth in previously underdeveloped market segments, such as a specialty chemical company diversifying into the medical hygiene products business. Effective risk oversight in the context of a major disruption thus requires boards to rise above their traditional monitoring role and develop a strategic stance to dealing with risk. Companies whose board members consider risk as an integral part of their business strategy rather than as an after-thought, are bound to have a competitive edge in building resilience for the future.

Effective risk oversight in the context of a major disruption thus requires boards to rise above their traditional monitoring role and develop a strategic stance to dealing with risk.

Adopting a long-term view

While extreme circumstances require that the board’s immediate attention be directed towards ensuring the company’s survival, directors must also adopt a long-term perspective, with a clear focus on strengthening the organization’s resilience in a sustainable and purposeful manner. Maintaining a long-term perspective might entail a delicate balancing act to reconcile the interests of shareholders and other important stakeholders (employees, customers, suppliers and the broader community), as well as responding to calls for greater clarity on the organization’s ultimate purpose. Take, for example, the recent public outrage about several financially strong international groups that (ab)used governments’ emergency response to the Covid-19 crisis to defer rent payments on their shops, with potentially detrimental consequences for small store owners. In times of severe turbulence and existential anxiety, it is particularly important for boards not only to protect their company’s short-term financial and operational performance, but also act as a beacon with a long-term view for the future on corporate purpose, social responsibility, and reputation.