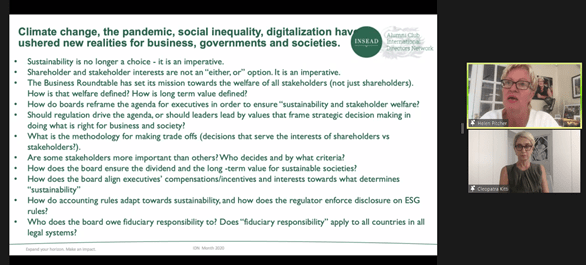

This is the third of a series of interviews intended to help our IDN members grapple with the ESG topic.

In this episode, we delve into the experiences of a seasoned ESG executive, exploring the insights she imparts to non-executive boards regarding ESG-focused interactions.

Kiku Loomis is a seasoned ESG professional bringing 20+ years of expertise in business and sustainability. Guiding global Fortune 500 companies, she strengthened sustainability programs and managed PVH’s human rights supply chain. Kiku directed traceability and certification at the Rainforest Alliance, later integrating Rainforest Alliance and Utz Certified. In 2000 she co-founded World Monitors, and launched the Fair Factories Clearinghouse, acquired by Worldly in 2023. Kiku is a director for the New York Solar Energy Society, former Foundry Theatre director, and on the Advisory Board for a biodiversity research project in Maui. She’s also a member of the ExCo of the INDEVOR Global Club and a founding member of the INDEVOR student club.

How do you perceive the significance of ESG for overall company governance and success?

My inclination is distinctly biased toward the complete integration of ESG into a company’s strategic framework. Over my 25-year career in sustainability, which began in my early 30s, I’ve consistently viewed ESG issues as pivotal business risks. Whether it’s human rights concerns or historical challenges like pollution, these have been part of our discourse for decades. ESG, in its current form, provides a more systematic and advantageous approach for companies, addressing risks while presenting new opportunities.

My focal point has always been ensuring a harmonious alignment of board strategy with the diverse opportunities encapsulated in ESG. For instance, aligning strategy with opportunities like electric vehicles or solar power significantly enhances the prospects of success. As we navigate the challenges of surpassing planetary boundaries, understanding dependencies becomes paramount, especially concerning supply chain risks. ESG serves as an invaluable framework, extending beyond immediate financial considerations to encompass societal values crucial for long-term health and value creation. While it may not yield immediate gains, I firmly believe that ESG plays a pivotal role in shaping a company’s medium and long-term success. This encapsulates the high-level, theoretical perspective I bring to the discussion.

What’s the key ESG misalignment between executives and non-executive board members, and how can non-executive boards effectively address and bridge this gap?

To start out: it is worth noting that not every board is the same! Boards may lack specific ESG knowledge, despite a noticeable rise in ESG discussions, especially in Europe. While board members may be aware of ESG matters, their proficiency in operational aspects could be limited. If an alignment gap exists, it might stem from a divergence in expertise between the board and the company. Turning to the second part, the ongoing discourse on ESG and the board’s agenda has prompted various training opportunities, though current materials often remain foundational. While non-executive board members may have a reasonable ESG understanding, the current imperative is to delve deeper into issues specific to their organizations. We’ve moved past the introductory stage, requiring executives and board members to engage in more profound discussions and tailored learning experiences aligned with their organizational nuances.

What crucial gap must boards address to achieve ‘ESG fitness,’ and how can they efficiently enhance skills in this area? What should Board Chairs prioritize to foster ESG competency among directors?

A significant source of strategic tension derives from a systemic conflict between traditional make-take-waste business models and ESG imperatives, and it calls for a reconsideration of practices, particularly in sectors like apparel, where a shift from linear to circular models is crucial. The challenge also involves the misalignment between financial incentives in capital markets and ESG principles, leading to decisions where financial interests clash with ESG perspectives.

Managing this tension falls to CEOs, who must present these complex issues for collective deliberation. Achieving complete alignment between ESG goals and financial objectives is a broad challenge requiring political attention, with the European Union’s regulatory initiatives seen as a potential model. For board chairs, the recommendation is to foster inclusive conversations across the organization, steering clear of siloed approaches. Integrating ESG considerations into the overall governance framework, whether through committees or alternative mechanisms, is crucial for a holistic and effective approach.

As 2024 approaches, what are the main ESG challenges for non-executive boards, and how can companies strategically address them?

The first imperative is fully integrating ESG into a company’s core strategy to avoid conflicting objectives, going beyond compliance to create a seamless integration into the broader strategy—a crucial safeguard amid evolving ESG landscapes.

A top challenge for multinational companies is to conform with emerging reporting requirements, including developments like the European Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive . This is a substantial challenge for global companies grappling with various jurisdictional reporting requirements. While it entails significant investment and meticulous processes, it’s vital to perceive it as more than compliance—viewing it as a catalyst for progress and valuable strategic insights. This era compels companies to collectively comprehend and fulfil ESG commitments for transparency and accountability.

Then, as we approach 2030, the focus must extend beyond climate commitments to effectively implementing them. Despite substantial challenges, the innovation spurred by collective ESG focus, particularly in climate action, presents significant potential.

For governance, fostering innovation and welcoming solutions aligned with ESG goals, especially in climate-related initiatives, is a strategic imperative propelling progress and integration into the core of business.

Lastly, one emerging concern for boards is the emerging prominence of Biodiversity and Nature loss, with a “nature positive” movement addressing the alarming loss of biodiversity and the impending sixth extinction.

The interviewer:

Dr. Pamela Ravasio is the founder and managing director of Shirahime Advisory, a Corporate Responsibility Governance boutique consultancy. She serves as fractional Chief Sustainability Officer for companies and advises boards on ESG and governance. With a background in roles like Global Stakeholder Manager, she played a key role in making the European outdoor industry a leader in future-proofing.

She currently sits on the boards of Polygiene AB and INSEAD’s International Directors Network.