The ethical and legal drivers of stakeholder primacy

As an independent director, to whom are you accountable? Should law or ethics be defining your decision-making position at the board?

By Karen Loon IDP-C and IDN Board Member

Over the past 18 months, the debate between shareholder versus stakeholder primacy has come under the spotlight.

With a heightened emphasis on the collective well-being of stakeholder communities worldwide, corporate boards are under intense scrutiny to find a delicate balance between maximising shareholder and stakeholder value.

The COVID crisis has revealed that focusing on shareholder value alone is no longer a viable option. Business leaders and corporate boards have a critical role in creating sustainable value for economic performance and societal progress. While stakeholder capitalism is the key to unlock inclusive sustainable growth, corporate boards must not overlook the associated risks involved in stakeholder governance.

Why is this important to independent directors?

Directors who operate in common law countries would be fully aware of their “fiduciary responsibility,” and use it broadly when discussing their responsibilities as independent directors.

However, not all countries have principle-based laws, which impacts the role of independent directors.

With the rising need for companies to focus on sustainability and digital resilience, board members need to consider whether their companies can afford to wait for regulatory and legal frameworks to be implemented (reactive). Alternatively, should market-driven strategies be based on stakeholder expectations and ethical considerations driving decision making (proactive)?

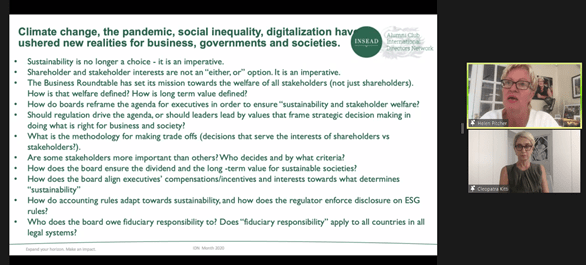

IDN members recently discussed these critical topics in a session led by Helen Pitcher OBE, IDP-C and IDN President, and Cleopatra Kitti IDP-C and IDN Cyprus Ambassador held on 8 September 2021.

New realities for businesses, governments and societies

Climate change, the pandemic, social inequality and digitalisation have ushered new realities for businesses, governments and societies.

Helen Pitcher OBE noted that in the past 15 months, there has been increasing and wide-ranging debate about the unintended consequences of corporate governance.

“Up until, maybe five or six years ago, the view was boards were there, basically to look at, and ensure that the investors were being appropriately safeguarded … It [was] very much [focused on] fiduciary duty,” Helen noted. This is the reason why, in the past, there were more former CEOs and accountants joining boards.

“Now days, it’s a much broader agenda,” she highlighted.

The pandemic has now accelerated all of this, with the need for companies and their directors to address all of the environmental, social, and governance issues, as well as fiduciary issues.

Helen mentioned that some have debated whether boards could say that they are only there to look after shareholders.

There has been a change in views towards companies thinking much more broadly about their culture and values and doing the right thing for the environment, society, etc, within an appropriate governance framework.

Further boards have a fundamental role in overseeing the sustainability of their organisations instead of just the here and now.

Adding to this, she said, “the executive is there for the here and now, within the context of the longer term. But typically, board directors serve for longer than the average CEO or CFO, so they are custodians of the future.”

“There was a recognition that there needs to be a change in how we link remuneration to these goals, to make sure that attention is being paid to them because we know what gets measured gets done usually. [A question is] how we still take account of the fiduciary responsibilities within the broader context of all stakeholders, and not just investors.” (Helen Pitcher OBE)

Areas for boards to consider

|

Increasing focus by larger investors, and other stakeholders on ESG and longer-term sustainability rather than shorter-term returns mean that boards need to openly and frequently discuss what this means for them.

Cleopatra Kitti added that boards also need to consider that stakeholders have increasing expectations of transparency. So, an important question for directors is how their companies track what they define are the right things to do, considering, for instance, the tensions between shareholder value and stakeholder value, sustainability and profitability, or cashflow preservation and sustainability.

She also noted that the upcoming COP26 (UN Climate Change) Conference in November 2021 is likely to increase investors’ focus on transparency and robust accounting mechanisms, leading to more clarity on how companies explore these areas. Further, the expected European Central Bank taxonomy on banks’ risk of capital may increase the cost of capital for certain types of industries.

“Not every legal system recognises fiduciary responsibility as a board obligation or responsibility. So, it brings us back to the point that this is about ethics and culture, and setting the tone at the top, more than a compliance or regulatory, for a regulated decision-making process. So, it’s up to the board to define in practice values of what is sustainable and the right thing to do.” (Cleopatra Kitti)

Areas which IDN members discussed included:

- Companies should do the right thing – pursuing sustainability and profitability and support shareholders and stakeholders need not necessarily be a trade-off.

- It is crucial to get ESG into the mainstream board agenda. Responsibility for this rests with both the board and management.

- Set the right KPIs as the wrong ones could lead to unintentional consequences. Some leading organisations now have integrated their ESG ambitions into their company ambitions and aligned this to the bonus system of executive committees.

- Reset remuneration levels for non-executives, given the increasing levels of responsibility and accountability they hold.

- Stakeholders will likely ask many more questions including on ESG at AGMs in 2022. Again, these are more likely to be in person rather than virtual.

In conclusion, as Helen Pitcher OBE summed up, “it is a hard topic but it’s not a topic that boards can avoid. It should be part of the strategic imperatives of the organisation.” It is a constantly evolving journey instead of a static situation on which boards need to go on.

Cleopatra Kitti added, “it’s an innovation journey. There is not a one size fits all and there are not prescriptive indicators or decision-making processes.”

Recommended reading and viewing

So Long to Shareholder Primacy

https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2019/08/22/so-long-to-shareholder-primacy/

Directors’ Oversight Role Today: Increased Expectations, Responsibility and Accountability—A Macro View

The Future of the Corporation: Moving from balance sheet to value sheet

http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Future_of_the_Corporation_2021.pdf

Measuring Stakeholder Capitalism: Towards Common Metrics and Consistent Reporting of Value Creation

http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_IBC_Measuring_Stakeholder_Capitalism_Report_2020.pdf

Measuring Stakeholder Capitalism: Full List of Revised Core and Expanded Metrics

https://weforum.ent.box.com/s/ieauc14olfozu1k8d4i6qovscu42a4dz

Webinar – “The End of Shareholder Primacy?”

https://video.insead.edu/playlist/dedicated/122053032/1_l1rr6r52/1_utyenvtn

INSEAD Directors Network (“IDN”) – An INSEAD Global Club of International Board Directors

Our Mission is to foster excellent Corporate Governance through networking, communication and self-improvement. IDN has 1,500 members from 80 countries, all Alumni from different INSEAD graduations as MBA, EMBA, GEMBA, and IDP-C. We meet in live IDN webinars and meet-ups arranged by our IDN Ambassadors based in 25 countries. Our IDN website holds valuable corporate governance knowledge in our IDN blog, and we share insights with our LinkedIn and Twitter followers. We highlight our member through quarterly sharing of their new board appointments, and once a year, we give out IDN Awards to prominent board accomplishments. We provide a peer-to-peer mentoring and board vacancy service, and we come together two times per year at the INSEAD Directors Forum arranged by ICGC. We also engage with ICGC on joint research.

INSEAD Corporate Governance Centre (“ICGC”)

Established in 2010, the INSEAD Corporate Governance Centre (ICGC) has been actively engaged in making a distinctive contribution to the knowledge and practice of corporate governance. The ICGC harnesses faculty expertise across multiple disciplines to teach and research on the challenges of boards of directors in an international context and to foster a global dialogue on governance issues with the ultimate goal to develop boards for high-performance governance. Visit ICGC website: https://www.insead.edu/centres/corporate-governance